A few years back a landscaper friend of mine sold his diesel work truck and bought a Prius. Even though the truck was more practical for his day to day work routine and actually got decent mileage, he'd been castigated by friends and clients for driving the "Beast" and felt the new hybrid would put a better polish on the image he was projecting. Coming back recently from three months of vacation, by all accounts his strategy seems to have worked.

Despite all the recently publicized problems Toyota has had recently, I like hybrids and the push to create more fuel efficient cars. During a period of the 70's that was dominated by enormous V8's, I was practically raised in the back of VW's that got triple their gas mileage. Kudos to my parents and to anyone today who wishes to conserve. What bothers me is the largely symbolic gestures businesses often make to ingratiate themselves to their customers.

Despite all the recently publicized problems Toyota has had recently, I like hybrids and the push to create more fuel efficient cars. During a period of the 70's that was dominated by enormous V8's, I was practically raised in the back of VW's that got triple their gas mileage. Kudos to my parents and to anyone today who wishes to conserve. What bothers me is the largely symbolic gestures businesses often make to ingratiate themselves to their customers.

Despite all the recently publicized problems Toyota has had recently, I like hybrids and the push to create more fuel efficient cars. During a period of the 70's that was dominated by enormous V8's, I was practically raised in the back of VW's that got triple their gas mileage. Kudos to my parents and to anyone today who wishes to conserve. What bothers me is the largely symbolic gestures businesses often make to ingratiate themselves to their customers.

Despite all the recently publicized problems Toyota has had recently, I like hybrids and the push to create more fuel efficient cars. During a period of the 70's that was dominated by enormous V8's, I was practically raised in the back of VW's that got triple their gas mileage. Kudos to my parents and to anyone today who wishes to conserve. What bothers me is the largely symbolic gestures businesses often make to ingratiate themselves to their customers. I've done it myself, struggling with the symbolism of plant selection.

Here's the deal: Invasive species can have devastating effects on ecology and many invasive species were actually introduced for one reason or another. In the last twenty years I've seen the green industry become more careful in the growth and selection of plant material. Locally, for example, that means fewer Russian Olives (Elaeagnus angustifolia) are being planted. This a good thing given how the now ubiquitous invader has out-competed native species in riparian areas. But I see an unintended consequence to this elevated sense of concern: tough, drought tolerant plants are getting a bad rap in Boise because in much milder areas (e.g. San Jose, Ca) they tend to jump the fence. The truth is I've stopped using some plants in my installations not because I believe there is any danger in planting these blacklisted plants in Boise, but rather out of concern for the image I'm projecting.

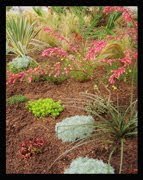

I'm coming to grips with the inherent silliness of that reasoning. I finished a small commercial installation this week using, among other ornamental grasses, drifts of Nasella tenuissima. Mexican Feather Grass, as it's known by it's common name, is a wispy, somewhat ethereal grass that's the plant equivalent of mood music. It also happens to be a grass that some have called on to be banned because of its potential to become invasive. An attentive gardener employee at the location brought this to the attention of the owner and sent him a link to an online Sunset Magazine article about N. tenuissima (go here to read it). The author, Sharon Cahoon, does a great job presenting the debate, concluding that the matter of invasive potential needs to be determined regionally.

Honestly, I would be reluctant to plant N. tenuissima anywhere that receives more than 16 to 20 inches of annual rainfall but in our arid, high desert I think it's a fantastic alternative to many of the thirsty plants designers seem to use over and over (hey, I'm gonna start my own blacklist). While it's true it will self seed a little within a garden, in 20 years of digging in Boise's dirt I've never seen it wander into a neighbor's bed or naturalize into a non-irrigated area. I've heard the same debate about other plants like Euphorbia myrsinites, another tough, evergreen perennial. While I believe there should be a careful vetting process for any new introduction, designers should also be careful not to eliminate tough, drought tolerant plants from their design palette simply to appear, err, correct.

The truth is, in Boise our options are pretty limited if we try to adhere to a strict definition of what constitutes a native plant. Even the tough-as-nails Celtis occidentalis, one of Boise's few true native trees, can only be found in limited areas naturally where, in a convergence of botany and geology, large sandstone or granite boulders collect and concentrate water for the trees. We just have to face it: if the Amazon basin represents one of the most biodiverse places on Earth, we sit somewhere on the other side of the spectrum.

The truth is, in Boise our options are pretty limited if we try to adhere to a strict definition of what constitutes a native plant. Even the tough-as-nails Celtis occidentalis, one of Boise's few true native trees, can only be found in limited areas naturally where, in a convergence of botany and geology, large sandstone or granite boulders collect and concentrate water for the trees. We just have to face it: if the Amazon basin represents one of the most biodiverse places on Earth, we sit somewhere on the other side of the spectrum.